My new article for Foreign Policy.

My new article for Foreign Policy.

In the days before he was gunned down in the doorway of his home in the Brazilian Amazon, environmental activist and union leader Chico Mendes knew he was a marked man. He had heard that a meeting of ranchers had been called to plan his death; he had seen, in his truck’s rearview mirror, the pistoleiros who followed him. Mendes told friends in December 1988 that he wouldn’t live until Christmas. He was shot dead a few days later.

In the 25 years since Mendes’s death, he has become an environmental icon, heralded as the “Patron of the Brazilian Environment.” ”In leading this struggle to preserve the Amazon, Chico Mendes had made a lot of trouble for a lot of powerful people,” Andrew Revkin wrote in The Burning Season, his book about Mendes. ”He was to the ranchers of the Amazon what César Chavez was to the citrus kings of California.”

But Mendes wanted something else. A month before his death he wrote, “I’d at least like my murder to serve to put an end to the impunity of the gunmen who have already killed people like me.”

That hasn’t happened. It is still incredibly dangerous to be an environmental activist in Brazil. And new research shows that violence against environmentalists has now escalated to an all-time high — not just in Brazil, but globally.

Between 2002 and 2013, at least 908 people were killed because of their environmental advocacy, according to “Deadly Environment,” a new report from the investigative nonprofit Global Witness. That’s an average of at least one environmentalist murdered every week, and in the last four years, the rate of the murders has doubled. In 2012, the deadliest year on record, 147 deaths were recorded, three times more than a decade earlier. “There were almost certainly more cases,” the report says, “but the nature of the problem makes information hard to find, and even harder to verify.”

In places like Myanmar, China, and parts of Central Asia, human rights monitoring is simply prohibited. In African countries like Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Zimbabwe, where clashes over resources have escalated, researchers say it is impossible to track the violence without in-depth field investigations, because governments haven’t documented the killings. The most vulnerable activists are those in indigenous communities in remote, rural areas who are facing off against much more powerful business interests in industries like mining and logging. Much of the world never hears about their struggles, or their deaths. In other words, where environmental advocates are most at risk they are least visible.

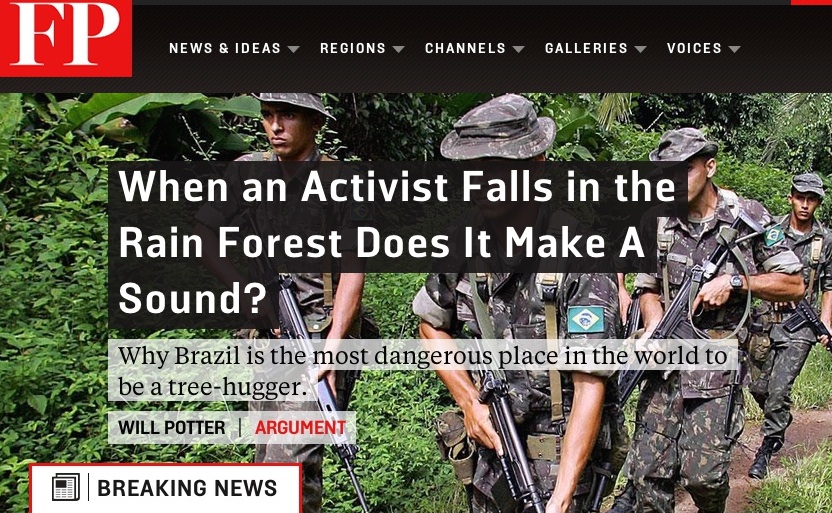

Despite these difficulties in collecting data, some patterns are clear. More than two-thirds of environmental murders globally were related to land conflicts. The most dangerous of these conflicts involve logging in the Amazon. But even after forested areas are harvested, the danger persists — the land is opened up to other industries like cattle ranching, and violence continues. Local communities that are not consulted about these business deals often don’t know what’s happening until they see the bulldozers. The law doesn’t recognize the land rights of indigenous people, and even if it did, these people do not have the legal resources to assert their rights. Those who remain and fight are threatened, not only by corporate thugs but by state security forces collaborating with industry.

Brazil, where land ownership is among the most concentrated and unequal in the world, accounts for about half of all recorded killings of environmental advocates, according to Global Witness. Although increased monitoring and reporting of violence might partially explain these high numbers, Brazil remains overwhelmingly more dangerous for environmentalists than other countries. Only partial data is available for 2013, but it shows that twice as many environmentalists were killed in Brazil than in any other country. As Brazilian political ecologist Felipe Milanez has said, “Violence is the instrument of local capitalism.”

In one high-profile case, Jose Claudio Ribeiro da Silva and his wife, Maria do Espirito Santo, were shot in a forest reserve by gunmen on a motorbike. The couple had worked producing nuts and oils for 24 years in the area, and when they became outspoken against illegal logging, they began receiving death threats. Both were members of the NGO founded by Mendes to preserve Amazon forests. And, like Mendes, da Silva predicted his own death.

The two men who pulled the trigger were convicted in 2013 — a rare victory in these kinds of cases — but the landowner accused of hiring the assassins walked free. This is typical: Only 34 people worldwide are currently facing charges for violence against environmentalists, and only 10 killers were convicted between 2002 and 2013.

The architects of environmentalists’ murders often have connections to powerful industries and politicians. “A fundamental challenge is confronting the widespread impunity enjoyed by political and economic elites who benefit directly from silencing environmental defenders,” Andrew Miller, advocacy director of Amazon Watch, said in an email. “The material authors of killing — the actual gunmen — are rarely caught and sanctioned, while the intellectual authors virtually never are.”

In the Philippines, which ranks third after Brazil and Honduras in terms of danger to environmentalists, there has been evidence of direct connections among industry, politicians, and gunmen. In 52 killings around the world, the culprits have been recognized as military or law enforcement personnel, though their identities remain unknown.

The lack of prosecutions has sent a clear message that environmentalists can be killed with impunity, according to Paulo Adario, a Greenpeace activist who campaigned against Brazil’s illegal mahogany trade. Brazil’s former president, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, gave him full-time bodyguard protection after he began receiving death threats in the early 2000s. “If you don’t punish crimes, you give a good signal for the future crimes,” Adario told Global Witness investigators. “If nobody was punished, and the last government gave in to pressure for an amnesty for everybody, why are they not going to do the same thing in five years from now?”

***

The threat facing environmentalists is direr, however, than even “Deadly Environment” outlines. The research is confined to 74 countries in Africa, Asia, and Central and South America, and it only includes murders. Nonlethal violence and intimidation, which is much more pervasive, are left out.

Jenny Weber is a longtime activist in Tasmania, where loggers have shot at and beaten environmentalists, blown up cars, and threatened lives. When two activists locked themselves in a car to blockade a logging road during a 2008 protest, a logger smashed out the car windows, dragged them out, and kicked them on the ground. The loggers were convicted of assault and sentenced only to community service.

“We have had firebombs thrown at blockade camps and vandalism of property,” Weber said in an email. “Though in comparison to fellow earth advocates across the globe I find that my experiences of violence over the past 15 years is not comparable.” Indigenous communities are facing such extreme violence, Weber said, that she is reluctant to draw attention away from them.

There is also a well-documented history of violence against environmentalists in Western countries, which isn’t included in the Global Witness report. In the United States, for example, a young environmentalist named David “Gypsy” Chain was killed in 1998 when a logger felled an old-growth tree in his direction. Moments before, the logger was recorded on video saying that if protesters didn’t move, he would “make sure I got a tree coming this way.” Chain was crushed and killed, and the local district attorney refused to press charges against the logger.

In England in 1995, Jill Phipps was protesting the export of live calves through Coventry Airport. She and about 30 other protesters were trying to stop the trucks by sitting in the road and chaining themselves together. Phipps was crushed beneath a truck and died.

Today in the United States and England, the mercenaries often hired to silence environmental activists are not assassins — they’re lawyers and lobbyists. Companies like TransCanada are briefing police on how to prosecute nonviolent pipeline protesters as terrorists. In Oklahoma, environmental activists are facing 10 years in prison because they unfurled a banner in a corporate headquarters and some glitter fell off the banner to the floor; police say they had no idea the glitter wasn’t a chemical weapon, so that amounted to a “terrorism hoax.” And now, multiple states are passing laws that make it illegal for environmentalists and animal welfare activists to videotape factory farms.

These legal and legislative tactics have been spreading. Could the violence that countries like Brazil have witnessed for years spread too? Perhaps the most troubling conclusion reached by researchers is that this is not only possible, but imminent. Since 2008, there have been a series of global food crises, and in that same period, murders of environmentalists have doubled. And signs for the future are bleak: A study by 22 prominent ecologists published in Nature in 2012 forewarns that the planet is nearing a point of dangerous, sweeping environmental changes — alongside massive population growth.

“These killings are increasing because competition for resources is intensifying in a global economy built around soaring consumption and growth,” the “Deadly Environment” report notes, “even as hundreds of millions go without enough.”